‘I Depict What I Know or Care About’

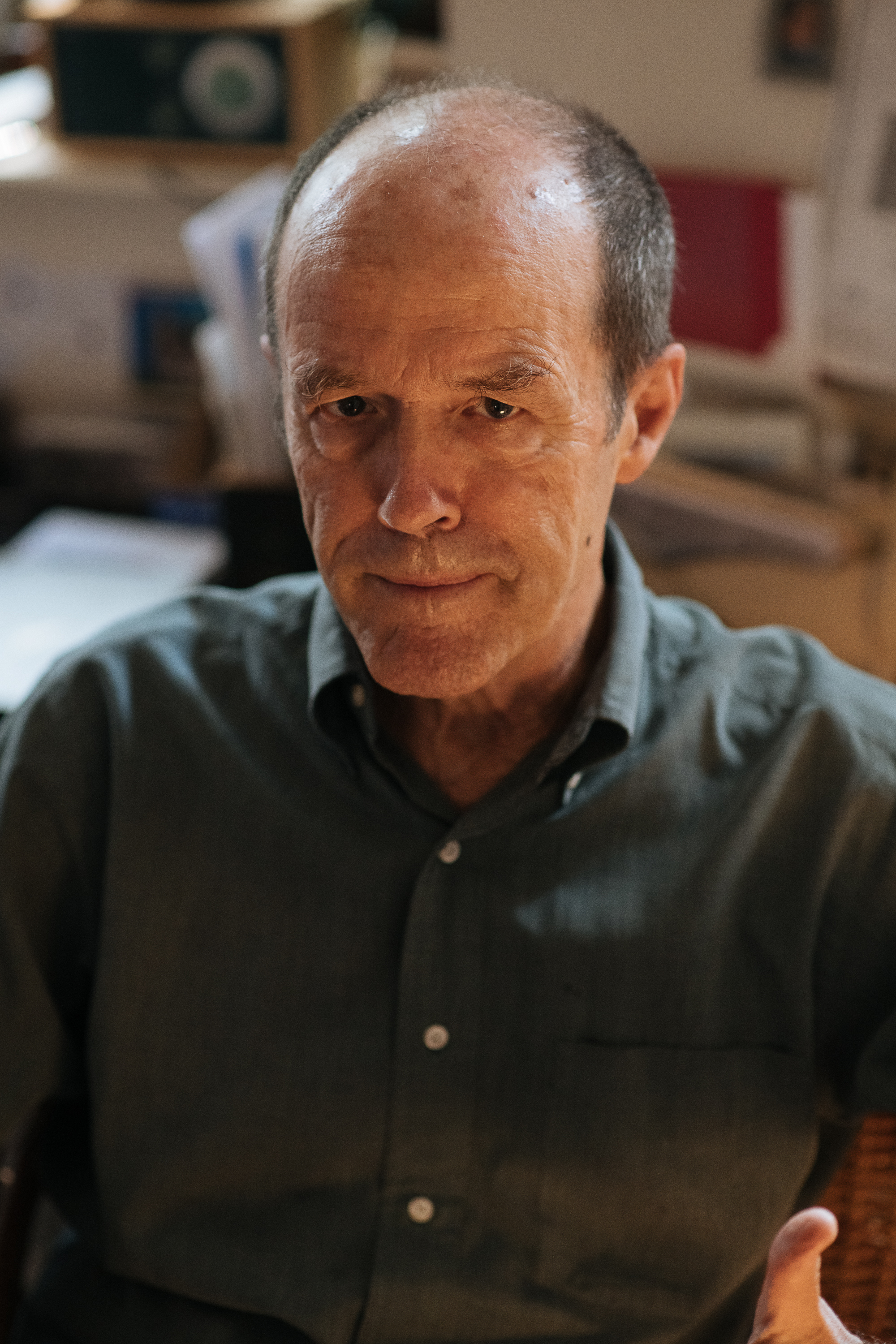

Sidney Lawrence

Artist & Georgetown Resident

At 71, Sidney Lawrence thinks a lot about time. How it’s changed him and his art. How he’ll spend the rest of it.

‘I realize I have to really understand that life becomes a little more in slow motion. It changes your outlook about deadlines and the need to produce. I approach it as one day at a time. But I’m not the same person I was.’

Born into San Francisco’s Ghirardelli empire, Sidney was 14 when his family sold the chocolate company that his great-great-grandfather founded in 1852. With no inclination to follow in his family’s footsteps, Sidney was grateful to emerge from the company shadow and pursue an early passion for art.

He won a school-wide contest in fourth grade, and later earned placement in a daily feature on the comics page of the San Francisco Chronicle, where his father worked after leaving Ghirardelli. Sidney still remembers the picture that landed him the gig—a style that would resurface throughout his adult work.

‘The picture is of a city. My interests were in perspective and distortion, and observing with my eye. I’m a depicter, not abstract. Even then, I liked to draw and I liked psychology of the figure, and how buildings appear to be alive and interact with us.’

Looking to his great-great-uncle for inspiration—a Norwegian artist known for his watercolor paintings of Yosemite—Sidney majored in art history at Berkeley and UC Davis. After graduation, he felt the itch to leave California.

‘When I was a kid, very young, I figured I’d go live somewhere else to make my world, like some of my ancestors had. I was aware of that impulse.’

Sidney received two job offers—one as a curator in Santa Barbara; the other, in communications for the Hirshhorn Museum. The latter paid $3,000 more a year, and Sidney followed the money.

‘I’d been to DC as an intern one summer, and it was hot and awful, but the city suited me. The museum community was terrific, and I could tell the art community was great. A lot of artists worked in museums, and eccentric collectors had these big parties for young people that I’d go to in Georgetown. There were a lot of characters.’

Newly married and launching a career that would span nearly three decades, Sidney felt the influence of the Hirshhorn artists he was publicizing. He began exhibiting his own work in Gallery K—one of several galleries around Dupont Circle at a time when the DC underground art scene was exploding.

‘My philosophy was, ‘Keep the prices low, invite everyone you know, and get them drunk.’’

Suddenly, both Sidney’s art and his personal life were at a crossroads.

‘People would pop from one gallery to another, and I would go to the parties of the artists whose work I liked. Then I would go home and work in my studio. For five years, I lived right near Booeymonger’s in Georgetown, in a very eccentric apartment where rain would come in through the roof. That’s where I started making my art after my wife and I split up. I was filling in my life with art.’

By the mid-80s, Sidney had met and began a loving partnership with Capitol Hill lobbyist Tom Birch—whom he married in 2010—settling into a 200-year-old home on 29th Street. He took new inspiration from their historic residence, and month-long trips to Denmark every August—experimenting with various mediums and techniques in his third-floor studio space.

‘I’ve always done ink drawings and paintings. In the beginning, the paintings turned into 3D. Then I started doing things with the frame; then that evolved into found objects. There would also be people in narratives, the things that interested me. The drawings had to do with my travels, mostly. I’d be drawing what I remembered seeing that day, or looking down into the city.’

Sidney’s interest in marrying found objects with the human narrative culminated in a 3.5-year project when he attended Bill Clinton’s second inauguration. With a vision of fusing a depiction of the former President’s face and an aerial view of Pennsylvania Avenue—inspired by a coronation painting he saw in Poland—Sidney went Dumpster diving to complete the work of art.

‘I found a string of those cooling beads from the back of taxi driver seats and I took it and pulled it apart, and glued them on the art as the people watching the inaugural parade. I made the Post Office building out of an ironing board I found in a Dumpster.’

By the time Sidney was finished, he had to cut the work in half to carry it out of his house—the focal point of the last big show he ever exhibited in Gallery K. It was a hard piece to let go of, in every sense.

‘The most attachment to every piece is during the process of making it. It’s like reading a book where you just don’t want it to end. It does and you’re a little depressed, and then you have to let it go.’

Sidney’s hometown, it seems, is the one thing he can never shake.

‘It’s the subject of a lot of my stuff. Whether I say so or not, the art is basically going back to San Francisco and the hills and the way it looks. I once made these portraits of my family with a frame that alluded to Chinese characters, and someone said, ‘That’s sort of San Francisco with the architecture.’ Writers write about what they know; I always depict what I know or care about.’

Since retiring from the Hirshhorn in 2003, Sidney has steadily worked in his studio, and has continued to occasionally exhibit—including several works on paper this fall at ENO Wine Bar. He says food is the new art; the days of going from one opening to another replaced by online sales and large art fairs.

For now, he’s content to travel with Tom, work when inspiration strikes, and return to the basics—currently teaching himself how to oil paint ‘like someone from the Renaissance.’

‘I used to beat myself up that I’m an old has-been, but most artists are better when they’re starting off and experimenting. My skill has become more refined, but you take more risks when you’re younger. I’ve been quite blessed though. To work isn’t necessarily to just be holding a paintbrush or a pen. I’m always looking around.’